This article was originally published in our 2021 Employment Law Issue.

I grew up in a suburban neighborhood in the 1990s that had everything one would expect: big front yards, kids biking in the street, a golf course, and, of course, an Avon lady. That was what we called her, anyway—the woman who came to the door at least once a month, wearing a business suit, smelling strongly of perfume, and carrying a briefcase full of products and magazines.

Most often, when she showed up, my mom would sigh, open the door, and allow her in to sit at the kitchen table and pitch all her latest items. Occasionally Mom would buy something: a lipstick that would eventually fall to the back of a bathroom drawer, nail polish for my sister and me, maybe some seasonal jewelry or eyeshadow. Some days, though, when my mom just didn’t have the energy to deal with a sales pitch, she’d shut off the television, tell us to sit quietly, and wait for the Avon lady to knock a few times before retreating to her car and moving on to the next house. At the time, I just assumed this was her job—that she was employed by Avon to sell to people like my mom, who stayed at home with her kids and had little time or patience for overpriced makeup. It was not until much later, when I myself ventured into the world of multilevel marketing, that I realized just what such companies were and why my mom generally worked so hard to avoid them.

I was in my mid-20s when an acquaintance asked me to join her in selling makeup, promising extra income from this seemingly easy work-from home side gig; at the time, I couldn’t see any drawbacks. My husband and I both had decent jobs but were eager to tackle a growing mountain of credit card debt and car loans, as well as start saving for fertility treatments. My mom and a handful of friends warned me that I was probably making a mistake by joining a multilevel-marketing company, but I was impetuous. Headstrong and confident, I was sure I’d make substantial profits from selling these products that, as far as I could tell, were decent if a bit overpriced. After all, I wore makeup every day, I had several friends on social media to whom I could sell products, and I had purchased from other network-marketing distributors in the past. I would no doubt sell enough to put a dent in my debts. But therein lay the problem: Selling the products was in fact the least effective way to make any money in multilevel marketing, especially on the lowest level.

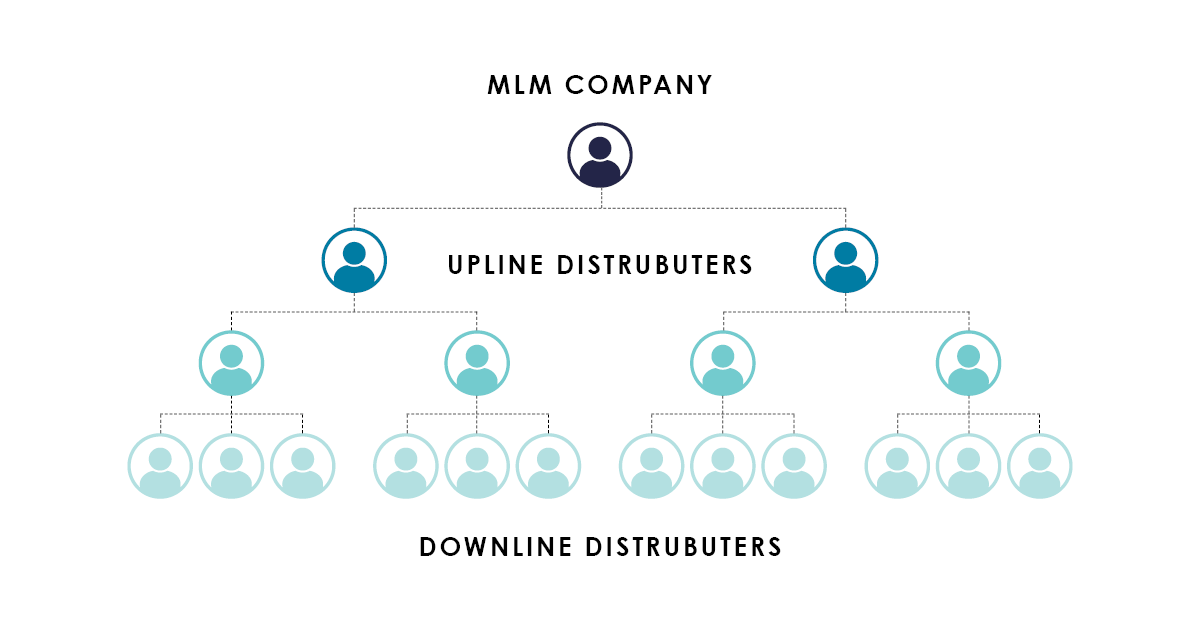

Direct sales, typically referred to as network marketing, multilevel marketing, or just MLM, is the selling of “products and services through a non-salaried workforce in a pyramid shaped commission system,” according to the Corporate Finance Institute (CFI). When you sign up to sell these products and invest in a starter kit (usually a few base items to evaluate or sell), you’re not hired as an employee of the company—rather, it considers you an independent distributor or contractor, and your commission is a small percentage of the products you sell. Joining an MLM means signing up under another distributor, considered your sponsor. Your sponsor and other distributors in higher levels above you—known as your “upline”—also make a percentage off your sales, as well as any items their other “downline” distributors sell. Signing up distributors and becoming part of an upline will then help you earn more money from all sales made by your downline. Some uplines even have so many distributors beneath them that they can cease selling altogether and rely solely on the sales made by their downline. The caveat? Recruiting people to sell these products in a saturated market (some 6.2 million Americans actively sell for MLMs), along with finding any kind of steady customer base, is extremely difficult.

Why, then, do people keep joining? According to the Management Study Guide, an estimated 50 million–plus people are involved in MLMs worldwide, with 70 percent of revenue coming from the U.S. alone. Multilevel marketing has been around nearly a century; the first company, a “sea-vegetable supplement” business called Wachter’s, was founded in 1932.

According to the Federal Trade Commission, 99 percent of MLM consultants will end up losing money.”

Today, goods sold via MLM include clothing, protein shakes, diet pills, cosmetics and skin care, shampoo, jewelry, cleaning products, and even financial services. Over the last several decades, with more than 1,000 companies on the scene, network marketing has evolved from door-to-door sales to selling directly through social media such as Instagram and Facebook. These platforms allow for hosting virtual parties, posting links and product photos, sharing live and prerecorded videos that discuss, demonstrate, and promote the items, and sending “cold messages” (direct communication, usually via social media, including scripted sales pitches) to friends, family, and complete strangers. One common theme linking this to the direct-sales tactics of the past, though, is that this outreach is less about selling products and more about recruiting others to sell. Without a downline, it is next to impossible to generate substantial revenue.

When I attempted to sell with the cosmetics MLM I joined, I spent roughly $500 of my own money on the initial startup kit, products to try myself, items for giveaways, and free gifts for paying customers. I even had to buy my own brochures and samples to give away. However, I was not willing to recruit anyone to work under me. I had joined in an effort to make money without understanding the true business model. Without a downline, the couple dollars I made on a few product sales were not adding up fast enough. A few friends had begrudgingly placed orders to support me, but I never pushed them to buy more or sign up to sell. My upline distributors were not fans of my honesty: I told people the truth about how I felt about the products, that many were not worth the price and better items were available at high-end cosmetics shops and department-store beauty counters.

My uplines questioned me often about my efforts to sign up other distributors. It did not take me long to realize this was not the moneymaking venture it had promised to be. I gave up after three months, barely netting $100 in total—some of which was a return on the money I had invested in merchandise myself and thus not profit.

Do MLMs Constitute Real Employment?

Get-rich-quick opportunities are rarely what they claim to be, and despite all the effort distributors put into them, they usually don’t make enough to be worth all the work. MLMs often push people struggling financially even deeper into debt. My being out $500 paled in comparison to the thousands of dollars many have lost trying to build a business through network marketing. Some MLMs even have startup costs of $5,000 or more, but like nearly all such companies, they offer no support and very little buyback money to distributors who are unsuccessful in sales. This is not uncommon; according to the Federal Trade Commission, 99 percent of MLM consultants will end up losing money, and per the Career Contessa, at least half of consultants will stop attempting sales within the first year.

To quit, all I had to do was stop selling and buying through my own website link, and after a few months, I was considered “inactive.” I didn’t have a boss to give two weeks’ notice to, I had no desk to clean out, and I certainly wasn’t planning to put this experience on my résumé. Though MLMs claim you can build a successful business from home, signing up as a contractor is not actually a career, and I wasn’t an employee. And because they don’t constitute formal employment, MLMs have no obligation to offer sales training, support, fixed salaries, or benefits, and they’re not liable for their distributors’ low sales or the money they have to spend on their own items.

Although they are legal, multilevel marketing companies are often intentionally vague about the specifics of how they operate. Pyramid schemes put a “primary emphasis on recruiting new participants with no genuine product or service actually being sold.” According to The National Law Review, “the critical difference between a legitimate MLM business and a pyramid scheme is that MLM’s revenues must come primarily from the sale of products and services to retail customers unaffiliated with the business.” From my own experience, though, my uplines never took issue with generating their own revenue on the products I sold to myself, and the goal was always to recruit others first and make sales second.

Not once, meanwhile, did I consider the potential legal ramifications. According to Reese & Richards PLLC, a law firm that specializes in MLM legal assistance and has worked with more than 1,500 direct-sales companies, MLMs work to sidestep the pyramid model by encouraging distributors to place large orders of inventory, which are often nonrefundable. Although the distributor makes a small percentage back on these purchases, the real value is for the sponsors and distributors in the upline, which make a generous profit. This evades the system’s real goal (recruitment) while allowing for hefty profits for those higher up the chain of command. Whether the downline is recruiting or buying large quantities of product, the desired result is the same: The more product sold, the more money the upline makes.

Further legislation aiming to rein in MLMs is inevitable, and direct-sales companies continue to try to elude legal trouble through crafty language and complicated business models. In general, network marketing appears relatively harmless, and it’s easy to see the initial appeal, with its promises of fast money and self-made business opportunities, but one must always proceed with caution around these companies. As a distributor, your rights are few. Legal recourse, workers’ compensation, and employment law will seldom be on your side. While it may appear as such, multilevel marketing is not an employment opportunity, and other than your own unsold merchandise, there are no severance packages when you get “fired.”