As a real-life legal who-done-it tale, it’s worthy of a John Grisham thriller.

The Alex Murdaugh case now unraveling in South Carolina has all the usual elements of a crackling cinematic potboiler. A lawyer from a prominent family firm around whom a string of cryptic deaths has swirled. He’s suspected of killing his wife and son, stealing from his own law firm and now perhaps having asked a former client to shoot him (leaving him with a minor headwound he survived) so that his surviving son could collect an eight-figure insurance payout.

But it doesn’t even end there. The family’s housekeeper died in 2018 under now-suspicious circumstances (for which her employers somehow received a $500,000 insurance settlement), and before he was killed by gunshot, Alex’s son Paul was piloting a boat in which a female friend died in a similarly suspicious way.

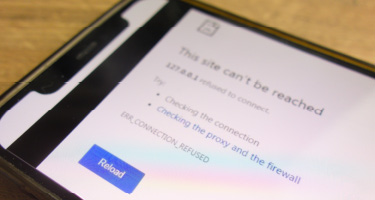

Perhaps more germane to the legal community, Murdaugh’s license to practice law was suspended by the disciplinary arm of the South Carolina Supreme Court, pending further investigation. The case shines a spotlight on the state-based system for enforcing lawyerly responsibility.

An American Bar Association survey found that there were just over 83,000 disciplinary cases brought before these state disciplinary arms in 2018, when there were 1.2 million licensed attorneys in the U.S.

“It’s a complaint-driven system and largely confidential,” notes Barbara Seymour, who served as prosecutor for the Office of Disciplinary Counsel to the Supreme Court of South Carolina for 17 years, serving as the Deputy Disciplinary Counsel from 2007 to 2017. She now assists other lawyers with ethical compliance. She notes that no one yet knows where the Murdaugh complaint originated. It could have arisen from a legal consumer’s complaint or just from the staff reading about the case in the media.

In her years in that system, she met many of her counterparts from other states, and they all had the same issue.

“These systems could all be better funded. There is a backlog of cases” due to a lack of staffing and budget to properly handle the workload. In South Carolina, for instance, which received 1,384 complaints in 2018, the disciplinary office of the state Supreme Court has just two investigators, eight lawyers and no paralegals.

As she compared notes with her colleagues around the country, “we all had the same complaints—we need resources. These are complicated matters.”

Few matters that have come before the South Carolina court’s disciplinary counsel have ever been more complicated than the Murdaugh case. But one must assume that its uniquely high profile means officials will somehow find a way to marshal the required resources to handle it.

John Ettorre is an Emmy-award-winning writer, based in Cleveland. His work has appeared in more than 100 publications, including the New York Times and the Christian Science Monitor.