Although the right to a jury trial is a hallmark of the American legal system, mediation and other forms of alternative dispute resolution have increasingly become the primary method of reaching cost-effective resolutions in most types of litigation. Notably, the restrictions brought on by the pandemic exacerbated the backlog of cases in courts that were already gridlocked due to budget cuts and other administrative challenges that existed long before Covid-19. Many trial and appellate courts in New York City advised litigants during the pandemic that it would take several years for their case to be heard following the completion of discovery, which itself can take several years to complete.

Indeed, even without delays, the cost and risk of a jury trial are often too high to justify for litigants in many kinds of cases. For example, a corporate or insured defendant might spend well in excess of six figures preparing for a trial after which it might still have to pay a multimillion-dollar verdict, whereas an injured plaintiff and his or her lawyer might invest much time, money, energy and emotion into a trial offering potentially no recovery at all. Additionally, a fair outcome at trial is often not possible based on the demographics of the jury pool, the political inclinations of the judge and other factors not within the control of the litigants and their lawyers.

In this atmosphere, mediation offers a path for litigants to have their case heard by a neutral third party in a timely and cost-effective manner. A mediator can assess the strengths and weaknesses of each party’s position and help them reach a resolution. The biggest benefits of mediation are that it is nonbinding and the parties can choose who will hear their case. The mediator is often a former judge known for resolving similar matters, sometimes in the same venue where the case is pending. Additionally, the cost to participate in mediation, typically a few thousand dollars, is far less than that of preparing for and conducting a trial. And even if the case is not settled at mediation, it offers a strong first opportunity for the parties to test their respective cases in a formal setting and see what they will likely encounter at trial without incurring the cost of one.

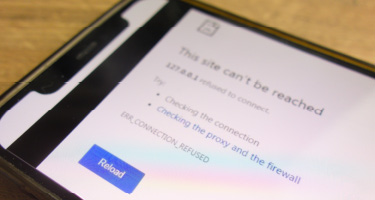

With remote video technology, which became more fully developed during the pandemic, lawyers and their clients have been able to participate in mediation and other court proceedings using Zoom, MS Teams and similar software. Although some courts attempted to use this technology to hold video trials, such use has not been widespread, at least not in New York City, where I primarily practice. Current technology enables mediators to seamlessly and confidentially discuss with each party the strengths and weaknesses of their positions and accurately communicate settlement demands and offers.

When selecting a mediator, lawyers often place too much emphasis on whether the neutral is inclined to favor one side or the other. However, since the primary goal of the mediator is to get all sides to resolution, a reputation for favoring only one side would not be helpful. More important would be whether the mediator has deep knowledge regarding the issues involved in the particular case—e.g., an aircraft accident versus a slip and fall in a shopping mall. Other mediators might be highly effective in cases involving the characteristics or demographics of the involved parties—for example, a mediator who can speak directly and plainly in the native language of one or more of the parties, or a mediator who is familiar with the technical terms and nomenclature of a specific industry or business. Of critical importance is whether the mediator can be trusted to convey information accurately and confidentially.

Another often undiscussed factor to consider is the mediator’s caseload. Although parties should obviously be wary of a mediator whom no one wishes to retain, by the same token, selecting a mediator whose schedule is always booked several months in advance has its drawbacks as well. Sometimes the mediator is so popular and therefore overbooked that parties can feel, rightly or wrongly, that their case did not receive the mediator’s full attention.

Emotions can run high at mediation, and lawyers in particular need to temporarily remove their 'trial blinders' to work toward a compromise resolution."

As with other vendors, prior experience will dictate whether the mediator should continue to be retained. The most effective ones will have tried-and-true strategies they employ at the appropriate stage of negotiations. These strategies, such as the use of bracketing or conditional offers or demands, become particularly important when the parties reach an impasse during settlement negotiations, which often occurs. The best mediators will go the extra mile to settle a case by continuing to urge the parties and their attorneys to reconsider their positions and by following up with both sides even if the initial mediation session did not result in a settlement.

Preparation is critical to increase the chance of a favorable outcome. Lawyers should submit concise written submissions to the mediator referring to key documents and testimony. These should highlight the primary strengths of their client’s case while also acknowledging its key weaknesses. It’s also vital that the decision-making individuals from all parties attend or be easy to contact during mediation to get their input and settlement authority. Additionally, in certain cases, a lien on settlement proceeds or some other third-party contingency may be a critical factor as to whether a case can be resolved. In such scenarios, it would be beneficial to resolve the lien or contingency prior to mediation or, alternatively, arrange for that third party’s decision maker to participate in mediation.

Emotions can run high at mediation, and lawyers in particular need to temporarily remove their “trial blinders” to work toward a compromise resolution. Lawyers must set realistic expectations for their clients and effectively manage them during mediation. Credibility is key, and the parties and their counsel need to take reasonable positions regarding liability and damages and avoid negotiating in bad faith. The same goes for making reasonable offers and demands during mediation and not significantly changing an offer or demand just beforehand. To this end, lawyers should be keenly aware of the sustainable jury verdict range in comparable cases involving the same or similar injuries or damages in whatever venue the case is pending.

Finally, the timing of mediation can be critical in determining whether a settlement can be reached. In cases where the liability issues are clear from the outset, mediation should be scheduled as early as possible prior to incurring significant litigation costs and while the parties and their counsel are not to set in their positions. Conversely, in a more mature case where there has been significant discovery, the best time to mediate would be after key discovery has been exchanged but before dispositive motions are decided. Parties should avoid waiting to mediate until the eve of trial given that there is no guarantee that the court will agree to reschedule the trial pending the outcome of mediation.

The bottom line: Mediation can be a very effective alternative to a costly and significantly delayed trial for resolving cases in a post-Covid-19 world. However, lawyers and their clients must be aware of the critical factors and preparation involved to ensure the best outcome.

John R. Oh is a seasoned litigator at FisherBroyles, LLP with over 25 years of experience resolving business and commercial disputes in a wide range of industries including aviation, commercial, interstate cargo, real estate, financial services and insurance. He is a graduate of Brooklyn Law School and admitted to practice in New York and New Jersey with pro hac vice admissions to the state and federal courts of many other states.