For more reasons than are probably appropriate to include here today, 2017 will be forever be burned into the memories of everybody in the U.S. immigration industry, and all HR and legal professionals who were involved in hiring and/or employing foreign workers in the U.S. No matter your political persuasion, 2017 turned out to not be anything like we all expected at the beginning of the year, following a historic presidential election result.

The year actually started out with some fairly good immigration news for businesses. We got a new I-9 Employment Eligibility Verification form from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services agency ( USCIS). The new form included some long-overdue changes, making it much more user-friendly for busy HR people. Simultaneous immigration regulation changes also tweaked several parts of the underlying employment verification rules. Those changes allowed for simple things like temporary work card extensions to be treated more reasonably, thereby avoiding common short-term (but always costly) gaps in work authorization for otherwise lawful workers in the U.S.

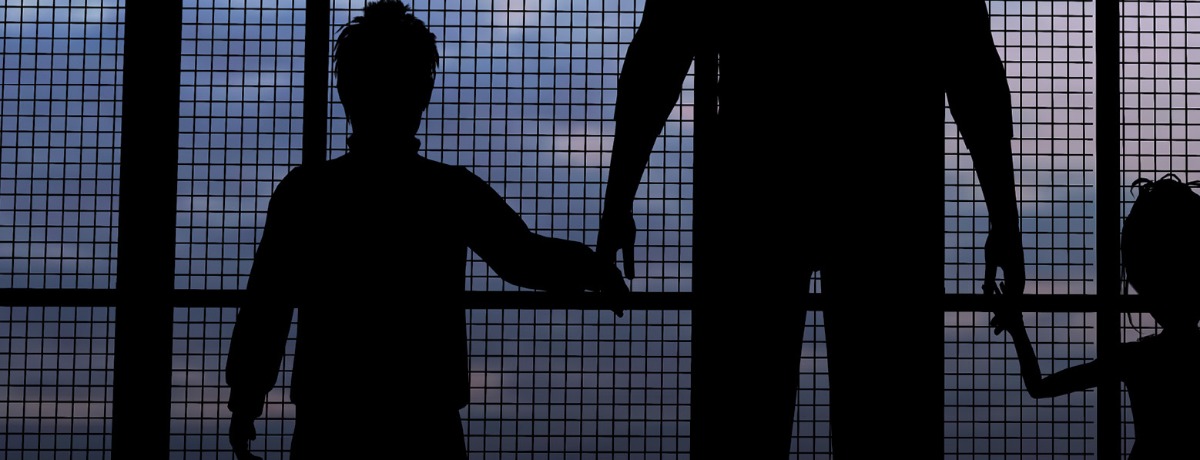

We all had our own opinions on the new president’s positions about a southern border wall, the danger posed by illegal immigrants in the U.S., and the problems with so-called “sanctuary cities.” Nobody was naïve enough to believe that the new administration wouldn’t attempt some changes to the U.S. immigration system (e.g., President Obama’s DACA program was squarely in their crosshairs). However, most business people also assumed that only Congress would change the core immigration laws and effect substantive change on the U.S. business community.

That “stay calm and hire (legally) on” message within the HR community was essentially how everybody felt going into the annual legal circus that is the H-1B cap lottery filing season on April 1. Few people in the immigration community had given much serious concern to yet another one of the president’s several executive orders: Buy American and Hire American. The order didn’t change any immigration laws (again, only Congress could), nor was it a regulation formally changing the government’s implementation of the existing laws. In fact, the small parts of the order referring to immigration at all simply consisted of general policy directives to federal agencies to ensure that they were enforcing existing laws (which many agencies initially took as an offensive insinuation that they’d somehow not been doing their jobs). However, by the end of the summer it became apparent that those same agencies had received directives to, in fact, alter long-standing processes and practices, the relative certainty of which U.S. business had come to rely on in a healthy economy, with significant skilled and professional labor shortages, across many industries.

Almost without warning, employers started seeing routine temporary work visa applications being suddenly denied by U.S. consulates across the globe. If any rationale was provided for these denials at all, it was usually just a vague reference to an undefined hire American preference for U.S. workers, which has never been a requirement in the U.S. law for those types of visas. Employers with European operations were particularly blindsided by a sharp uptick in denials of E and L class work visas for top managers and critical technical personnel being temporarily transferred to the U.S. Similar results were being reported from the U.S. borders and international airports. And then, a deluge of so-called requests for evidence started arriving from the USCIS immigration agency, in connection with those H-1B cap lottery petitions employers had filed on April 1.

After celebrating the “good luck” of having their petition selected in the Kafkaesque one-in-three odds of the H-1B cap lottery, many well-intentioned companies were hit with long, rambling 10-page letters from the USCIS demanding copious amounts of additional evidence to prove that the company was a genuine employer with a valid professional job offer. Also included in those requests were lengthy arguments that entry-level but still entirely professional workers were somehow no longer eligible for H-1B work visa sponsorship; this again, despite no changes in the immigration laws or regulations at all. Employers and their attorneys have been scrambling for months to respond to these queries, wasting an enormous amount of time, energy, and resources on something that would have been virtually unheard of in the two prior decades. Informal estimates of the number of such novel USCIS requests this summer were in the thousands, and many of those H-1B petitions are still not yet resolved today. A Wall Street Journal article last month summed up the situation well, including this quote: “The goal of the administration seems to be to grind the process to a halt or slow it down so much that they achieve a reduction in legal immigration through implementation rather than legislation.”

So, what does all of this mean for employers and legal professionals in 2018? The short answer is that nobody knows. Until Congress takes up meaningful immigration reform legislation, it’s likely the various federal agencies will continue to take actions that make the U.S. immigration system effectively unusable for many employers. The economic impacts of that on U.S. industry are obvious. For the busy HR professionals in the day-to-day trenches, that translates to a need to be hyper-diligent about their company’s immigration compliance, to be significantly more proactive about routine work visa sponsorships than they’ve ever been in the past, and to work even more closely with competent immigration counsel and help business units and their critical foreign workers to navigate an ever-changing landscape of unwritten government rules. It remains to be seen if Congress will finally wade back into the immigration reform debate. Either way, it will definitely be another interesting year in global mobility.

------------------

Christian Allen is a senior attorney in Dickinson Wright’s Troy office, where he practices exclusively in the area of immigration law. He has extensive experience guiding employers of all sizes and in all industries through the maze that is the U.S. immigration system. Chris can be reached at 248-433-7299 or CAllen@dickinsonwright.com.