There is no going back; we are past the pixel of no return.

Technological advances like generative AI (“GAI”) have created a paradigm shift in society, impacting the practice of family law in surprising ways and raising important ethical and legal questions.

As technology pervades all aspects of modern life, family law practitioners must adapt to new challenges and opportunities.

Technology touches every aspect of our lives, influencing how we communicate, work and play. Smartphones, Facebook, Zoom, Netflix and Uber are seamlessly integrated into our daily lives, and new advancements are emerging rapidly.

Unsurprisingly, the societal shifts brought about by technology have also profoundly influenced the practice of family law.

Pushing the Boundaries

As clients’ social media accounts, computers and cellphones have become treasure troves of information, practitioners can now turn to advancements in artificial intelligence to help conduct electronic discovery of this evidence and streamline document review.

At the same time, GAI is pushing the boundaries of legal research and the drafting of documents filed with the court.

However, entering this brave new world requires a crucial caution: the use of this technology must adhere to professional responsibility, legal ethics, and client confidentiality.

While it offers numerous advantages, it also introduces significant inherent risks.

Everywhere All the Time

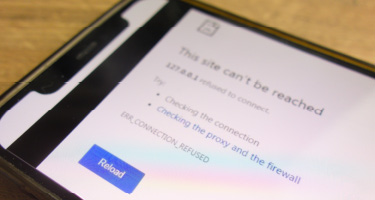

Electronically stored information (“ESI”) is commonly used in family law cases.

Kept on electrical and digital devices, including computers, cellphones, tablets, digital cameras, GPS devices, hard drives, thumb/flash drives and servers, ESI such as social media posts, text messages and emails are standard evidentiary fare for divorce and custody cases.

Posts to platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and X often contain photographs, location check-ins and similar information that reveals the lifestyle, behavior and relationships of the parties and can be extremely useful as impeachment evidence.

Emails and text messages also have evidentiary relevance in establishing patterns and tone of communication while also showing any agreements or disagreements between the parties, as well as anger, threats and possible danger.

In addition, footage from security cameras can offer visual evidence of occurrences and actions relevant to the matter. At the same time, GPS data from smartphones and other devices can establish travel patterns and locations that may help dispute or support parties’ claims.

Using ESI Responsibly

The use of ESI must adhere to the discovery and ethical rules relevant to the jurisdiction where the case is ongoing, as these rules can differ from one state to another.

In addition, digital evidence must be authenticated to be used in court, and attorneys must also consider any applicable ethical and legal considerations relating to its usage.

Attorneys must also ensure that sensitive data related to parents and children is securely stored and managed.

Consider cases that involve disputes concerning child custody and parenting time: extremely sensitive topics are often addressed, including allegations of substance and alcohol abuse, as well as mental health disturbances.

Such information should be protected under strict confidentiality protocols and secure data-handling practices that prevent unauthorized access, ensure trust and promote the integrity of the legal process.

Family Law Adopts AI

Family law attorneys are also increasingly turning to artificial intelligence-based technologies to improve the efficiency of document management, electronic discovery and rote administrative tasks.

Using these tools can be extremely helpful in sorting, categorizing and searching the mountains of information that often hallmark family law matters and is viewed as generally acceptable, as long as the appropriate safeguards are in place to ensure client confidentiality.

However, extreme caution is required when using GAI to perform legal research and draft court documents.

Although the lure of using GAI to enhance efficiency may be strong, it is fraught with significant ethical minefields.

A Cautionary Tale

Many likely remember the swirl of news stories last summer reporting on a case in a Manhattan federal court that offered a textbook example of the perils that can arise from using GAI in legal research and writing.

The lawyers in Mata v. Avianca, Inc. had used ChatGPT as their sole research source for authority to support their client’s personal injury case. Counsel then filed a legal brief containing fictitious case citations that were generated by the chatbot and signed the documents “under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is true and correct.”

After the court discovered that counsel had used ChatGPT to generate the non-existent case law relied upon in their brief, it imposed a $5,000 fine pursuant to Federal Rule of Procedure 11, holding that although “[t]echnological advances are commonplace and there is nothing inherently improper about using a reliable artificial intelligence tool for assistance,” Rule 11 “impose[s] a gatekeeping role on attorneys to ensure the accuracy of their filings.”

The court concluded that counsel “abandoned their responsibilities when they submitted non-existent judicial opinions with fake quotes and citations created by the artificial intelligence tool ChatGPT, then continued to stand by the fake opinions after judicial orders called their existence into question.”

A legal AI cautionary tale, the Mata incident illustrates that technology must always meet the highest ethical standards of our profession in researching and drafting legal documents.

This begs the question: What exactly are those “standards” for using GAI?

Searching for an Answer

The American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility inched toward attempting to answer that important question in July by releasing its first formal opinion addressing the growing use of GAI in the practice of law.

Formal Opinion 512 opens with the following summary statement: “To ensure clients are protected, lawyers using generative artificial intelligence tools must fully consider their applicable ethical obligations, including their duties to provide competent legal representation, to protect client information, to communicate with clients, to supervise their employees and agents, to advance only meritorious claims and contentions, to ensure candor toward the tribunal, and to charge reasonable fees.”

This 15-page opinion identifies general ethical issues involving the use of GAI—including the four “C”s: Competence, Confidentiality, Communication, and Candor—and provides helpful guidance in navigating these considerations.

Risk v. Reward

Specifically, ABA Model Rule 1.1 obligates lawyers to provide competent representation to clients and requires them to exercise the “legal knowledge, skill, thoroughness and preparation reasonably necessary for the representation.”

The opinion cautions attorneys that although GAI has “the ability to quickly create new, seemingly human-crafted content in response to user prompts,” this potential increase in efficiency must be balanced against the inherent risks in its use, including its ability to “hallucinate” responses and inability to “understand the meaning of the text they generate or evaluate its context.”

Although GAI “may be used as a springboard or foundation for legal work … lawyers may not abdicate their responsibilities by relying solely on a GAI tool to perform tasks that call for the exercise of professional judgment.”

Confidentiality Considerations

Further, pursuant to ABA Model Rule 1.6, a lawyer using GAI has “the duty to keep confidential all information relating to the representation of a client, regardless of its source, unless the client gives informed consent.”

The opinion cautions that “[b]efore lawyers input information relating to the representation of a client into a GAI tool, they must evaluate the risks that the information will be disclosed to or accessed by others” and that “[s]elf-learning GAI tools into which lawyers input information relating to the representation, by their very nature, raise the risk that information relating to one client’s representation may be disclosed improperly.”

Clients Communication

In addition, ABA Model Rule 1.4 addresses a lawyer’s duty to communicate with clients and builds on a lawyer’s legal obligation as a fiduciary, which includes “the duty of an attorney to advise the client promptly whenever he has any information to give which it is important the client should receive.”

With specific relevance to GAI, the opinion points to Model Rule 1.4(a)(2), which states that a lawyer shall “reasonably consult” with the client about how the client’s objectives are to be accomplished and that “lawyers must disclose their GAI practices if asked by a client how they conducted their work, or whether GAI technologies were employed in doing so.”

Consider the Courts

Finally, the opinion highlights that in addition to their ethical responsibilities to clients, lawyers using GAI likewise have ethical responsibilities to the courts.

ABA Model Rule 3.1 provides, in pertinent part, that “[a] lawyer shall not bring or defend a proceeding, or assert or controvert and issue therein, unless there is a basis in law or fact for doing so that is not frivolous.”

Similarly, ABA Rule 3.3 clarifies that lawyers cannot knowingly make any false statement of law or fact to a tribunal or fail to correct a materially false statement of law or fact previously made to a tribunal.

Finally, Rule 8.4(c) provides that a lawyer shall not engage in “conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation.”

Therefore, the opinion concludes, “output from a GAI tool must be carefully reviewed to ensure that the assertions made to the court are not false” as “[e]ven an unintentional misstatement to a court can involve a misrepresentation under Rule 8.4(c).”

Tectonic Change

In sum, technology has created a paradigm shift in society that impacts the practice of family law in many ways.

Undoubtedly, this technology has the beneficial potential to make aspects of practice more efficient and will lead attorneys and firms to innovate and adapt.

However, technology like GAI requires constant vigilance to ensure adherence to ethical rules, confidentiality of client matters, and accuracy of results.