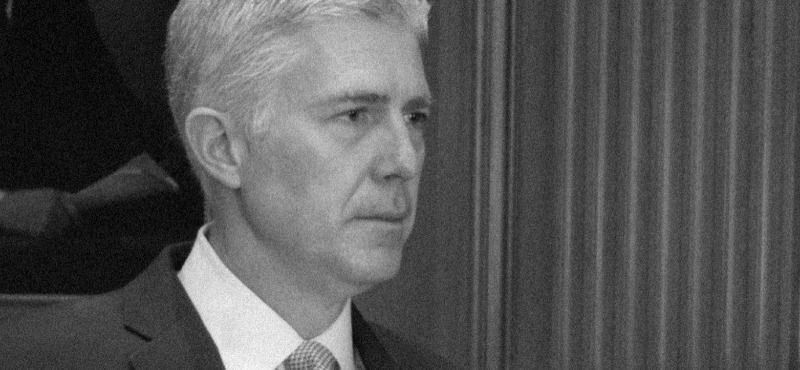

Justice Neil Gorsuch wasn’t a member of the U.S. Supreme Court back in 2004, when the justices ruled in Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain (124 S.Ct. 2739) that in certain limited circumstances, foreign nationals can use a 1789 law, the Alien Tort Statute, to sue in U.S. courts for violations of the law of nations. Though the Sosa opinion, written by then-Justice David Souter, agreed that Congress intended the ATS to grant jurisdiction for “a relatively modest set of actions,” the court cited two modern examples of ATS cases: Filartiga v. Pena-Irala (630 F.2d 876), a suit by Paraguayans accusing a former Paraguayan official who had moved to the U.S. of torture; and In re Estate of Marcos Human Rights Litigation (25 F.3d 1475), in which torture victims from the Philippines sued former president Ferdinand Marcos.

The defendants in both of those cases were, of course, not from the United States. So you might assume that the Sosa decision resolved the question of whether Alien Tort Statute plaintiffs can sue non-U.S. citizens. Michael Elsner of Motley Rice certainly did. Elsner represents thousands of foreign nationals who sued Arab Bank under the ATS for allegedly financing terror attacks in Israel. A divided 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the ATS claims in 2016, holding that corporations such as Arab Bank cannot be defendants in ATS suits. The Supreme Court, as you probably recall, had taken up that question in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum (133 S.Ct. 1659) but ended up sidestepping corporate liability in a ruling that focused on whether the ATS applies to conduct outside of the borders of the U.S.

Last April, the Supreme Court granted Elsner’s clients’ petition for review of the Arab Bank case to decide the question it abandoned in Kiobel: Does the statute allow liability for corporate defendants? Elsner and his co-counsel brought in Jeffrey Fisher of the Stanford Supreme Court clinic to argue their case. In all their briefing and argument prep sessions, Elsner told me, no one gave serious consideration to the idea that when Congress enacted the ATS in 1789, it intended the law to preclude suits against foreign defendants.

Justice Gorsuch obviously prepped differently. At oral arguments on Tuesday in Jesner v. Arab Bank, the justice brought up a 2011 article by law professors Anthony Bellia of Notre Dame and Bradford Clark of George Washington. In “The Alien Tort Statute and the Law of Nations,” published in the University of Chicago Law Review, the professors argue that when the First Congress enacted the ATS, its main concern was heading off military reprisals for wrong perpetrated against foreigners by U.S. citizens. “The original meaning of the statute is relatively clear in historical context: the ATS limited federal court jurisdiction to suits by aliens against U.S. citizens,” the paper argued.

Gorsuch asked both Fisher and Brian Fletcher, assistant to the solicitor general, why the Supreme Court shouldn’t accept Bellia and Clark’s scholarship and defer to Congress’s intent in adopting the ATS. Under that line of reasoning, Arab Bank would be off the hook not because it’s a corporation but because it’s a foreign defendant. (The Justice Department agrees with the Jesner plaintiffs that corporations can be liable under the ATS but contends this particular case should be dismissed.)

Fisher and Fletcher answered Gorsuch by citing the Supreme Court’s Sosa and Kiobel cases, which both involved foreign defendants. “The government’s point of view is that that is not the understanding of the statute that we understand this court to have taken in Sosa or Kiobel,” Fletcher said.

Fisher, on behalf of the plaintiffs suing Arab Bank, used part of his rebuttal time for additional colloquy with Gorsuch on ATS history. One of the original justifications for the law, he said, was to provide redress for piracy – and those anticipated pirate defendants weren’t citizens of the U.S. Moreover, Fisher said, the statute specifies aliens have a right to sue but says nothing restricting whom they can sue. “If (Congress) had wanted only U.S. nationals to be defendants, you have to ask the question why Congress wouldn’t have been specific,” Fisher said.

Fisher co-counsel Elsner told me it seemed ironic for Gorsuch, an avowed textualist, to read Congressional intent into statutory silence. “Textually, that seems inconsistent,” Elsner said.

Justice Gorsuch had no questions for Arab Bank counsel Paul Clement of Kirkland & Ellis, whose challenge was explaining to the court’s liberal wing, and, in particular, to an openly skeptical Justice Elena Kagan, that foreign nationals victimized by corporate misconduct can find recourse through means other than ATS litigation against the company itself. It’s notable that Clement did not pick up on Justice Gorsuch’s theory in his answers to questions from the other justices.

I don’t want to suggest that Justice Gorsuch’s unexpected line of questions is going to tip this case. Though the justice’s research shows an impressive willingness to pursue scholarship even beyond the copious briefing in this case, the other justices didn’t seem to bite at the theory that the ATS is restricted to U.S. defendants. Gorsuch’s theory, assuming he wasn’t just playing devil’s advocate, puts him on Arab Bank’s side in the case, but it doesn’t seem likely to persuade his colleagues to join him.

Many of the reporters who observed Tuesday’s argument, including Reuters’ Lawrence Hurley, said Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Samuel Alito and Anthony Kennedy appeared to be worried about the diplomatic implications of allowing foreign nationals to sue corporations. From their accounts, it sounds like Arab Bank has a far better chance of winning than I would have thought possible, given Kiobel’s implication that corporations can be liable under the ATS if their conduct significantly touches and affects the U.S.

But if Arab Bank does win, it won’t be because of Justice Gorsuch.