This article was originally published in our 2021 "Women in the Law" Business Edition on June 7, 2021.

The first job Karen Evans ever had was at risk. She was a 15-year-old junior counselor for 10-year-old girls at a YMCA summer camp in her hometown of Wilmington, North Carolina. Counselors who did well the first session could then work through the season. “I knew I couldn’t tell my mother and grandmother that I had lost my job,” she recalls. “I and my co–junior counselor were not guilty of telling those young girls the stories that frightened them so much they ran screaming into the night.”

The ax was imminent, and Evans knew it. She approached the camp supervisor directly and explained who was responsible for the horrific tales that let to the campsite fiasco. If anyone had to be fired, she argued, it ought to have been the senior counselors; she and the other junior should have been welcomed back for the duration. Evans rested her case. “You, young lady,” the supervisor told her, “should be a lawyer.”

The innate confidence on display that day had surfaced in Evans even earlier. “I’ve always been a take-charge personality,” she muses. Growing up, she and her close-knit clan of cousins all lived within a few blocks of her grandmother. “My mother tells the story of 5-year-old Karen being the teacher in a pretend school on the steps of my grandmother’s house,” she adds. “My older cousins were my willing pupils.” They were indulging her, perhaps, but Evans has long believed that “leadership starts with where we have been, and the people who serve as our mirrors.”

She was nurtured in the cocoon many African-Americans spun deliberately to shield their children and loved ones from the harsher aspects of society. In Wilmington, there was still only a thin veneer over the abhorrent 1898 racial violence that killed dozens and inflicted enormous property damage.

As a child, Evans didn’t ride public transportation; wherever she needed to go, she had to wait for an adult to drop her off and pick her up. “My uncle worked in a drugstore that had a soda fountain,” she recalls. “He would always say to us children, ‘Don’t come in—I’ll bring you drinks.’ We didn’t know then that the soda counter was segregated— we just knew our uncle liked to treat us to drinks outside.”

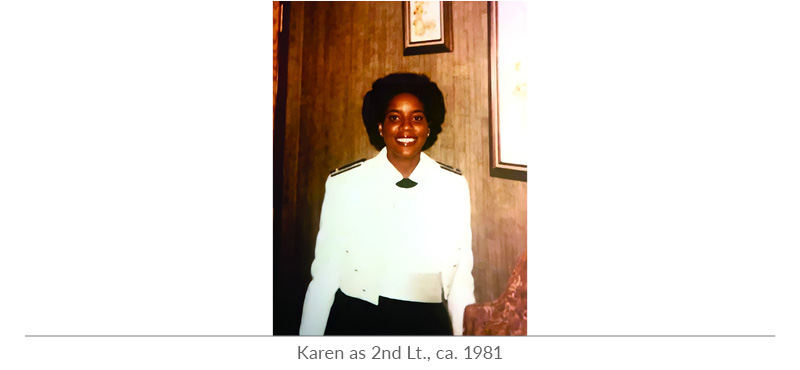

Her mother was a nurse’s aide who had hopes her daughter would go further than she had in the same line of work. In 1980, Evans graduated from East Carolina University’s nursing school and chose the Air Force to pursue her career as a registered nurse. “I saw the military as a pathway that rewarded performance. You know what you have to do, and you know what the results should be.”

She became a commissioned officer and rose to the rank of captain. “Aim high and fly,” she says, citing an Air Force motto she has embraced throughout her life and legal career. Rank itself, she observes, provides useful perspective on leadership. “I’ve seen doctors talk to nurses in all manner of ways, for example, but as a captain, they had to address me as a military officer.”

There was more in play than just the respect for authority that rank commands, she explains. “As an officer in the U.S. Air Force Nurse Corps, I was taught ‘each one, see one, do one, and teach one.’ My takeaway: A leader shares knowledge and teaches others. This resonated because it was consistent with my core values. It enabled me to find a path to leadership in a way that was natural for me.”

Military service also imbued Evans with the relentless discipline she now pours into her legal work. “Our life experiences forge the unique leadership skills that we bring to the table,” she says. “We must embrace the empowering life lessons that shape us. It is those experiences and lessons learned that help each of us develop authentic leadership.”

Although rank had its benefits, the demands of nursing—“a tough profession,” she says—took a toll. After six years, she began to consider other careers that could reward her drive and intellect. Her eureka moment came while watching two lawyers present at a seminar. “They were competent enough, but it wasn’t difficult to see myself in that role.” She adds, with a laugh, “If I knew where they were today, I would thank them.”

She earned her law degree in 1990 from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Law. “I didn’t know any lawyers personally when I went to law school, certainly not any Black lawyers. It’s so important to have someone to talk to. You never know how a few words may make a difference.”

As an officer in the U.S. Air Force Nurse Corps, I was taught each one, see one, do one, and teach one.

Mentoring is in Evans’ DNA; she has always sought to help people through instruction and example. “My nursing background and desire to help others allowed me to develop compassion and empathy, which deeply inform my personal style of leadership.”

From 2007 to 2012, Evans taught at the University of the District of Columbia David A. Clarke School of Law, D.C.’s public law school that is committed to the public interest, using the legal system to help those in need and serve the community.

Her core advice: Never stop learning. “Losing often teaches us more than winning,” she says. “Losing requires deeper self-reflection. Mistakes can be a learning experience. Discern when to ask permission and, if necessary, when to seek forgiveness.

“Sharing expertise is key to fulfilling our leadership potential,” she continues. “Surround yourself with people who possess leadership qualities and positive traits you would like to attain. Learn what works for them. Develop systems that work for you by yielding reliable results but still allow for creativity.

“Embrace experiences lived and lessons learned. These provide a true path to your unique and authentic leadership style and will reflect the values you hold and deem important.”

After a lifetime spent demanding excellence of herself—and sticking up for justice and the truth since the days of that long-ago YMCA camp—Evans has arrived at a plateau of self-realization: “Life experiences shaped the leader I am today and [still] strive to become. We all, me included, have the potential to become better leaders.”

Khalil Abdullah provides consulting, writing, and editing services on a range of policy issues. He is a former executive director of the National Black Caucus of State Legislators. He was a senior writer/ researcher for the Summit Health Institute for Research and Education, Inc., and managing editor of the Washington Afro-American Newspaper. He joined New America Media as the first director of its Washington, D.C. office and assisted in policy briefings and workshops for ethnic media. As a national editor for NAM, he also contributed as a writer. He is currently a contributing editor to Ethnic Media Services among other clients.