Based upon the line that divides the states of New York and New Jersey, a patient injured as a result of medical malpractice will see a dramatic difference in both the viability of their case and the way it will proceed to trial.

A patient’s medical malpractice claim in the state of New Jersey is subject to the affidavit of merit statute, N.J.S.A. 2A:53A-26 to -29, and the New Jersey Medical Care Access and Responsibility and Patients First Act, N.J.S.A. 2A:53A-41. The initial purpose of these acts was to require a plaintiff to reach “a threshold showing that their claim is meritorious, in order that meritless lawsuits readily could be identified at an early state of litigation.”[1]

These acts place an obligation on the plaintiff and the defendant involved in malpractice cases to retain qualified experts. However, the goal of the affidavit of merit statute has recently been whittled away by the courts, and to such a degree, that the New Jersey courts are now dismissing timely filed medical malpractice case in New Jersey may be dismissed because the plaintiff’s expert physician’s credentials do not exactly match the credentials of the defendant’s expert physician―even when both the plaintiff’s and the defendant’s expert physician have demonstrated expertise in the area of medicine at issue.[2]

Compare this with New York state law, which does not require a medical expert to be a specialist in a particular field in order for the expert to testify about accepted practices in that field. Instead, the expert must simply possess the requisite skills, training, education, knowledge or experience from which it can be assumed that the opinion rendered is reliable.[3] The New York courts widely recognize that there is an overlap between medical specialties―a distinction that, unfortunately, the New Jersey courts seem to no longer acknowledge.

The regulations on experts testifying in New Jersey malpractice cases call for the experts to meet specific criteria outlined by the Legislature. In particular, the affidavit of merit statute, N.J.S.A. 2A:53A-26 to -29, states that in order for a plaintiff to proceed with a malpractice claim in New Jersey, the plaintiff must submit an affidavit from an expert who “is a specialist or subspecialist recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties or the American Osteopathic Association and the care or treatment at issues involves that specialty or subspecialty… the person providing the testimony shall have specialized… in the same specialty or subspecialty.”

In addition, if the party is “board certified and the care or treatment at issue involves that board specialty or subspecialty,” then the expert must either be board certified or sub-certified in that same specialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties or the American Osteopathic Association or credentialed by a hospital to treat the condition or perform the procedure.

On the other hand, in order for an expert to testify in New York, the attorney for the plaintiff must simply certify that he has consulted with a physician who believes there is a reasonable basis to support his claim. See CPLR §3012-a.

The dramatic difference between these two states in obtaining the opinion of a qualified medical expert has made it much more difficult for those injured in the state of New Jersey by medical negligence. It is not only harder to find an expert to support the plaintiff’s claim, but it is also more challenging to proceed to trial. Moreover, the cost associated with bringing a medical malpractice claim in New Jersey has dramatically increased, which has likely led to the reduction of meritorious malpractice claims being brought.

Notably, the costs of defending a medical malpractice case have also increased. It should also be noted on July 22, 2014 (effective Sept. 1, 2014), the New Jersey Legislature amended the statutory attorney contingency fee scale (R. 1:12-7), providing for an overall increase in the attorney’s fees. In New York, only medical malpractice cases are subject to a statutory contingency fee scale (Judiciary Law §474-a), which has not been amended in almost 30 years. Despite the complexity and cost of litigating a medical malpractice case, the attorney fees in New York are far less than those allowed in other non-medical malpractice related claims, and in the state of New Jersey.

Discovery Procedure

The discovery procedure between New York and New Jersey is also different. In New Jersey, statutory interrogatories (or questions submitted under oath) must be answered by the parties in all malpractice actions. In New York, the use of interrogatories in personal injury and medical malpractice claims is prohibited by statute (CPLR §3130), unless the party demanding the interrogatories elects to waive the opponent’s deposition or obtains permission of the court.

In both states, the parties involved in a lawsuit routinely ask questions at a deposition. In New Jersey, expert reports and depositions are required by rule. Compare this with New York, which prohibits depositions of non-party treating physicians, unless the nonparty's testimony is necessary, and/or that the nonparty's testimony is the only means of gaining the sought after information.[4]

Moreover, in New York, the names of experts retained by the parties regarding issues of malpractice and medical causation are kept confidential; that is to say, these experts are not required to issue reports or take depositions. In fact, the names of the proposed experts and their depositions are only required when both sides agree to disclose their respective experts for depositions. CPLR §3130(d)(ii). In lieu of an expert report, New York attorneys must prepare a summary of the expert’s anticipated testimony pursuant to CPLR §3101(d), along with a summary of the proposed expert’s credentials, materials reviewed, and the subject matter of the expert’s anticipated testimony.

As a result of the limitations on expert discovery in New York, the costs associated with litigating a case in New York are more reasonable than those associated with litigating in New Jersey. One of the main reasons for New York’s more reasonable cost of litigation is that there is no need to compensate the experts for the time in preparing medical reports of for deposition testimony. Moreover, experts in New York have more latitude when testifying, as they are permitted to opine on areas that overlap with their medical specialty, or even, arguably, outside of their medical specialty. This is not the case in New Jersey.

Likewise, the timing of the expert disclosure remains different between the states. In New Jersey, all discovery must be conducted within the court-imposed deadline or discovery-end-date (R. 4:24-1). Rule 4:24-1(c) was amended to provide that “absent exceptional circumstances, no extension of the discovery period may be permitted after an arbitration or trial date is fixed.” Indeed there are very limited exceptions in New Jersey where discovery can take place after the discovery-end-date has expired.

In New York, expert information in medical malpractice cases is routinely disclosed at or near the time of trial. This is because the statute governing disclosure of expert information CPLR §3101(d)(1)(i)) does not specify when a party must disclose its expected trial experts upon receiving a demand. Discovery in New York is typically deemed complete after the filing of a note of issue and certificate of readiness. Post-note of issue discovery may only be sought if a party can demonstrate unusual or unanticipated circumstances and substantial prejudice absent the additional discovery (22 NYCRR 202.21 (d)). While a stringent standard, a far more liberal one than seen in New Jersey.

Statute of Limitations

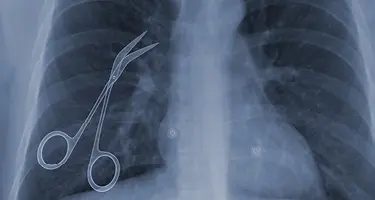

Finally, the rules regarding the statute of limitations are distinct among the two states. While some states have a discovery rule, e.g., where the person could reasonably have learned of the malpractice, there is no discovery rule in New York. New York limits the discovery rule to situations where a foreign object was left in the patient’s body following a surgical procedure. In New York, a malpractice claim must be filed within 2 ½ years from the date of the malpractice (not when it was discovered) or in cases where the individual is treating for the same illness, injury or condition with the physician who caused the harm, the statute begins to run when that treatment ends. In New Jersey, however, the statute begins to run at the time the malpractice could reasonably have been discovered by the plaintiff. In essence, it is a true discovery rule.

The vast difference between the statute of limitations in these states is often seen through the experience of those diagnosed with cancer years after a certain test, or in those cases where a physician failed to identify the cancer at a time when it should have been discovered. In New Jersey such a claim would be viable; in New York, it would not. Despite this harsh injustice, the New York courts are constrained to interpret the statute literally, and the Legislature has failed to make this most needed change.

Similarly, in New Jersey, the statute of limitations for derivative claims―those brought by parents of infants or by a spouse―track with the statute of limitations for the injured party. However, in New York, derivative claims are subject to the 2 ½-year statute of limitations with almost no exceptions to extend the statute beyond that time.

Perspective

It is our opinion that, having practiced as medical malpractice litigators in both states for more than 20 years, the discovery rules in New York, while not perfect, are inherently fairer to all parties. To further our point, it is worth noting that at the time this article was written, an article published in the Jan. 14, 2015, New Jersey Law Journal professional liability supplement called for a change in the way the affidavit of merit statute has been recently interpreted by the New Jersey courts. The article calls for a declaration that the statute be “declared unconstitutional, amended, or construed sensibly and realistically…The alternative is that the courts, the bar, and the parties will be doomed to forever waste an enormous amount of time and resources on the process, instead of determining the merits of our cases.”

------------------------------------------------------------

Jeff S. Korek is a partner at Gersowitz Libo & Korek and a past president of the New York State Trial Lawyers Association.

Michael A. Fruhling is a partner at Gersowitz Libo & Korek and a sitting governor of the American Association of Justice – New Jersey.

[1] In re Hall, 147 N.J. 379, 391 (1997),

[2] See Nicholas v. Mynster, 213 N.J. 463 (2013) [holding that plaintiff’s expert, board certified in internal medicine, who was credentialed to treat the condition in issue, carbon monoxide poisoning, was disqualified from testifying against a defendant family medicine doctor who was the “attending physician” assigned by the hospital. See also Meehan v. Antonellis, A-1040-13 (App. Div. 2014).

[3] See Ozugowski v. City of New York, 90 A.D.3d 875, 877, 935 N.Y.S.2d 613, 615-16 (2d Dept. 2011).

[4] See Ramsey v. New York University Hospital Center, 14 A.D.3d 349 (1st Dept. 2005); Dioguardi v. St. John’s Riverside Hospital, 144 A.D.2d 333 (2d Dept. 1988); Michalak v. Venticinque, 222 A.D.2d 1060 (4th Dept. 1995); compare Schroder v. Consolidated Edison Company, 249, A.D.2d 69 (1st Dept. 1998), where the First Department declined to follow the Second Department’s decision in Dioguardi, supra, to the extent it requires a defendant to show “special circumstances” in order to warrant the taking of a non-party physician’s deposition.

The original article was published in the New York Law Journal on Wednesday, March 18, 2015.