Anthony Kennedy has been a long-time skeptic of “Chevron deference,” and following his leave from the Supreme Court, the judge-made doctrine for judicial review of administrative agency actions may be on the line.

On his way out the door, in a solo concurrence in Pereira v. Sessions, Kennedy left a parting gift for those who believe the powers of the “Administrative State” have been creeping to a point where constitutional separation-of-powers principles may have been compromised. Kennedy shouted from the mountaintop that “it seems necessary and appropriate to reconsider, in an appropriate case, the premises that underlie Chevron and how courts have implemented that decision.”

If Justice Kennedy is replaced by a jurist that shares his doubts about Chevron deference, the doctrine’s days are numbered—and we probably will start to see a gradual dismantling of the doctrine.

As an attorney practicing regularly before the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Justice Kennedy’s unusual and purposeful effort to call the question caught my attention. As an expert agency vested with substantial policy making jurisdiction under the Federal Power Act, Chevron deference is usually front and center whenever they are taken to court for judicial review of a final agency action. So what might a Supreme Court roll-back of Chevron deference mean to the FERC’s administration and implementation of the Federal Power Act?

The Basics of Chevron Deference

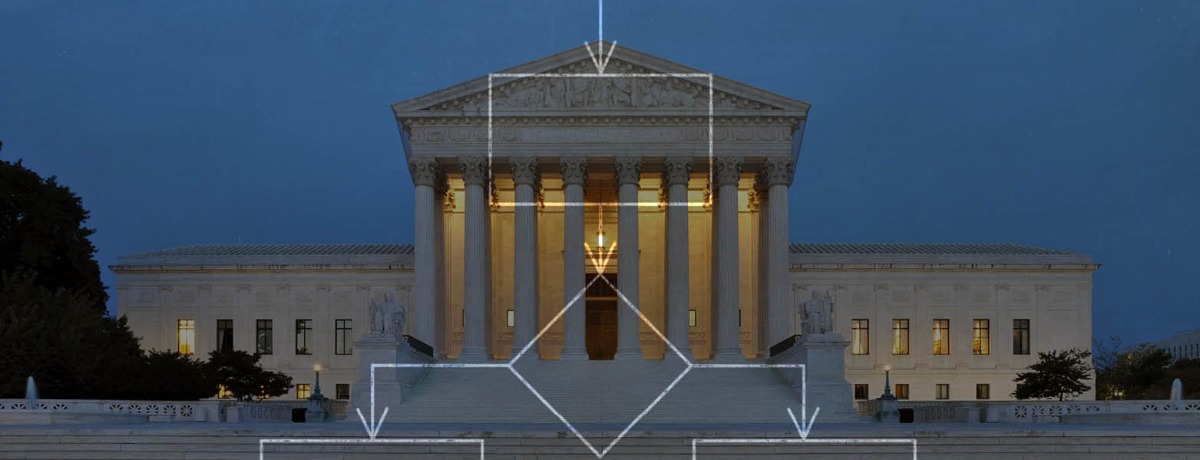

The basics of Chevron deference are relatively straightforward. First, there is Chevron “step zero:” Does the governing statute (such as the Federal Power Act) clearly delegate interpretative authority to the agency (such as the FERC)? If so, move to “step one.” Under Chevron step one, the question is whether the statutory language is clear after applying traditional canons of interpretation. If so, then the statute controls. If not, then move to “step two.” Under Chevron step two, the question on judicial review is whether the agency interpretation is reasonable. The Supreme Court has not indicated much concern in several recent opportunities to express doubt about Chevron deference to the FERC with respect to rate making and what is “just and reasonable.” When it comes to the FERC’s construction of the Federal Power Act to define the scope of its jurisdiction, the Supreme Court has artfully dodged the question lately.

Then there is the “Auer deference,” which involves an extension of the foregoing principles to an agency’s interpretation of its own regulations. The Auer extension is of interest to agencies like the FERC who preside over mountains of direct regulations (regulations it has promulgated) and indirect regulations (tariffs and business practices approved by the FERC and placed “on file” by regulated utilities).

The FERC is Probably Fine When Interpreting the Federal Power Act

Congress has vested exclusive jurisdiction to regulate wholesale power sales and interstate (high voltage) transmission related services in the FERC. Recognizing the specialized expertise and industry knowledge required to effectively regulate this essential industry, the Federal Power Act is remarkably general. Its mandates to the FERC are especially broad and general in nature, giving the agency tremendous authority to breathe life into such amorphous terms as “undue preference” and “just and reasonable.” Given such broad terms, Congress has intentionally delegated interpretative authority to the FERC, clearing Chevron steps zero and one. It would seem that the FERC is on solid ground with Chevron step two whenever it is interpreting and applying the Federal Power Act.

But many of the cases and controversies before the FERC do not involve the application of the Federal Power Act. Much time and effort is expended on examining the FERC’s indirect regulations—the tariffs “on file” by public utilities. This is where the Auer extension comes into play.

The Auer Extension Could be in Trouble

The rates, terms, and conditions under which power generation facilities may supply generating capacity for and inject power into the high-voltage grid, and under which system users can “wheel” or transmit that power within or through a balancing authority area are set forth in detailed “tariff records.” As of the date of this article, there are literally thousands of tariff records and rate schedules “on file” with the FERC. These are not simple affairs. To give the reader some idea of the size and scope of these tariff regulations, consider these random facts: the Midcontinent Independent System Operator’s tariff is over 6,000 pages and PJM Interconnection’s “Manual No. 35” has 155 pages dedicated exclusively to “Definitions and Acronyms.” You get the idea. These tariffs are massive beasts. And there are hundreds of them.

It is one thing for appellate courts to defer to the FERC on whether a particular approach to cost allocation for interconnecting and providing transmission service to new wind farms is “just and reasonable” under the Federal Power Act. It is quite another for appellate courts to defer to the FERC with respect to details of interpreting tariff requirements that it did not even write but merely approved. Many of these tariff requirements, which are akin to contracts, are very vague and give tremendous authority and discretion to Regional Transmission Organizations. For this FERC lawyer, it will be very interesting to watch upcoming confirmation hearings and to see if there is any distinction drawn between traditional Chevron deference and the Auer extension. If you are wondering whether Auer is on the rocks for the FERC, take a look at this statement issued last fall with respect to the denial of a certiorari petition involving the Department of Transportation by Chief Justice Roberts and joined by Justices Gorsuch and Alito.

--------------------

Lyle Larson counsels clients involved in all aspects of the electricity industry, from power plant development and operation, wholesale power sales tariffs and issues, transmission tariff arrangements, and supply to retail consumers. Among other things, Lyle serves as Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) counsel to over 25 separate market-based rate sellers and qualifying facilities that own or control over 50,000 MW of generation (coal, gas, nuclear, solar, wind, and biomass) in 16 states, in each interconnection and every Regional Transmission Organization (RTO) region.