There has been considerable discussion concerning the challenges that diverse attorneys have faced in the law. Pair that with the many discussions about the range of experiences diverse individuals have had in the construction industry, and a level of insight into the life of a diverse construction attorney begins to form. Little public attention, however, has been placed on the diverse construction lawyers’ unique experiences, whether in private practice or an in-house counsel role. In fact, there is a dearth of published information addressing diversity in construction law at all. Let’s take a closer look at the current state of the challenges and opportunities facing the growing pool of this highly talented group.

As an obvious yet central starting point, construction lawyers, by definition, serve the construction industry. Construction is an industry with a well-recognized history that would not be characterized as diverse. That’s changing now, with outstanding leadership in this regard being offered by some of the nation’s largest builders. But overall, diversity in the construction industry is in its relatively early stages of evolution, and the industry was slower to adopt these practices for a variety of reasons.

In turn, diverse construction lawyers essentially face a two-tiered challenge. First, diverse construction lawyers face the prospect of penetrating the legal profession as that profession was and continues to evolve in expanding diversity itself. Secondly, the clients that construction lawyers serve were and remain in the process of addressing diversity challenges in that industry, more so than other industries.

The emerging issues of diversity in the construction industry are being addressed by leading general contractors in the industry, as well as in organizations such as The National Association of Women in Construction (NAWIC) and national conferences like Groundbreaking Women in Construction (GWIC). Leading companies across the construction industry, at all levels of leadership, are realizing the benefits and attributes of increased diversity. Improving diversity through expanding the potential pool of talent across all business lines has become a key consideration for construction companies, particularly those entering and expanding across the U.S. and in international markets.

Financially, this consideration is driven by numbers—the understanding that diversity has generated a competitive advantage for construction companies. As a result, more construction companies are addressing the role diversity currently plays in the construction industry, how diversity has assisted premier construction companies in creating and maintaining a competitive advantage, and how emerging trends in diversity are likely to alter the landscape at all levels of the industry, including the law firms that service the industry. That effort by construction companies ultimately serves diverse construction lawyers who face the latter rung of the two-tiered challenge described above.

Law firms are moving beyond the concept of diversity as being “the right thing to do,” focusing instead on the business, economic, and societal benefits it brings. The business and economic benefits law firms see are derivative, in part, from the reality that their clients are increasingly diverse. Clients that seek diversity internally generally seek diversity externally, and we are beginning to see that factor take hold in the construction industry—made manifest by the fact that in-house attorneys at construction companies are beginning to make diversity a consideration in the selection of outside counsel, in turn helping pave the way for diverse construction lawyers.

Meanwhile, although diversity in hiring has expanded at the law firm level in general, hiring decisions alone are not enough to facilitate a future for diverse construction lawyers. Statistics show that many law firms are relatively successful in attracting diverse lawyers, but the second rung faced by the diverse construction lawyer and by law firms—retention—becomes the next challenge. For example, although women comprise 45 percent of law firm associates, they only account for 19 percent of equity partners in private law firms.

"Leading companies across the construction industry, at all levels of leadership, are realizing the benefits and attributes of increased diversity."

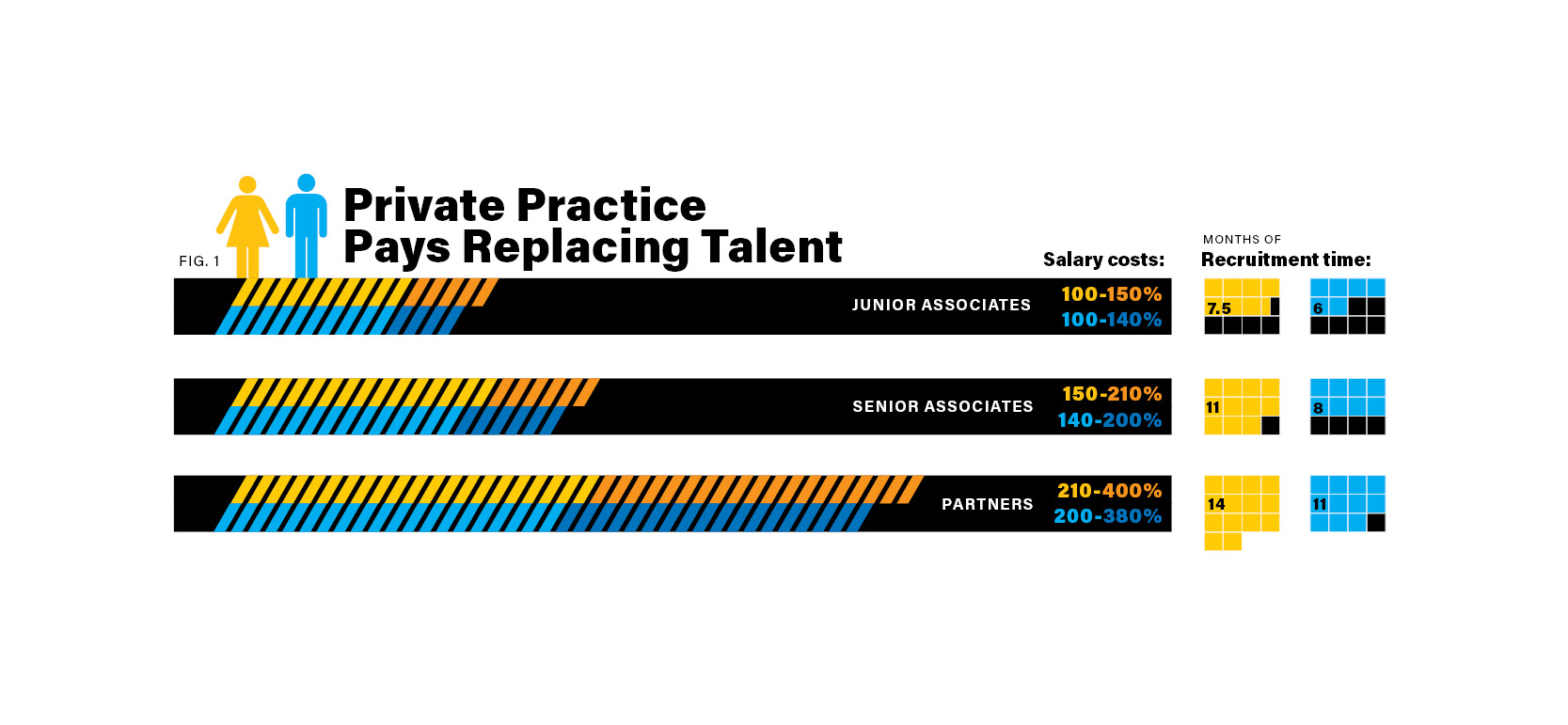

Although statistics are not available, many have noted that the construction industry has been particularly active in recruiting diverse construction lawyers from private practice to in-house positions at construction and design firms. While diverse candidates have moved to successful in-house careers, this reality has presented an added challenge for private law firms in expanding diversity at higher ranks. Compounding the challenge, studies have shown that it costs 100 to 150 percent of salary to replace female junior associates, 150 to 210 percent to replace female senior associates and a staggering 210 to 400 percent to replace female partners—an increase of roughly 10 to 20 percent across the board compared to the cost of replacing male counterparts. (See FIG.1)

Certain studies have shown that while 91 percent of law firm leaders believe their firms are active advocates of gender diversity, only 62 percent of women lawyers thought the same thing—a marked difference in perception that sends a signal about one key issue: a law firm’s culture.

A culture genuinely supportive of the development of diverse candidates is central to a law firm’s success in the retention and growth of a diverse team, in construction or any other area of the law. That culture may be demonstrated by providing the tools and opportunities, together with support necessary to achieve the goals. Focus and attention must be given not just to developing competencies aimed at creating skills for success inside the law firm, but with the clients the firm represents as well. Training, even leadership training, for diverse individuals is not enough. Such training is valuable, but the real power comes when it is coupled with real opportunities external to the law firm.

A culture of support for diverse lawyers can also be demonstrated by training, of course. Initiatives and programs that encourage diversity, diversity training, and promotion of diverse individuals within the firm and with clients are surely beneficial. For these initiatives to work, it is imperative that the formal programs be coupled with a genuine commitment by the firm’s leadership. These initiatives are, in turn, in furtherance of the firm’s culture. There is no one-size-fits-all solution. Firms should tap into the creativity of their own lawyers to create solutions that can work within the context of a firm’s culture that genuinely embraces diversity.

"Law firms are moving beyond the concept of diversity as being 'the right thing to do,' focusing instead on the business, economic, and societal benefits it brings."

Education about inclusion across all levels of the firm is a valuable component of training. Acceptance and Commitment Training (ACT), often being used now, has shown to be effective. A behavioral intervention, ACT is designed to create more “psychological flexibility” by helping individuals come into greater contact with others’ personal experiences while undermining the dominance of mindless thoughts and gut reactions, also known as “implicit bias.” Implicit bias is everywhere. It occurs when a well-intended individual’s unconscious assumptions get in the way of objectively gathering information or assessing another individual or situation. This bias thrives in the void of self-awareness.

Implicit bias does not involve overt prejudices but rather learned biases gained from life experiences. Every human being possesses implicit bias. Cognitive study has shown that just 10 percent of cognitive activity is conscious thought. The other 90 percent are automatic, non-conscious brain processes (biases, gut feelings, emotional reactions, social judgments) which occur parallel to intentional conscious thought. These biases are subtle and insidious because they often take the form of unintentional, unconscious thoughts of which the individual is unaware.

ACT does not aim to change thoughts, feelings, or biases. Rather, it accepts these non-conscious brain processes as a natural part of the human condition. ACT instead educates people on their own psychological flexibility (or inflexibility) and shifts one’s relationship to external events. The individual is educated to identify implicit bias and to pause without judgment so the cycle of reaction can be interrupted.

The focus on learning the skills for taking effective action in the face of long-established automatic thoughts and feelings is what makes ACT an effective tool in diversity and inclusion—and it is precisely for these reasons that ACT is effective with lawyers who are taught to value their objectivity and cognitive thought. A firm’s understanding of implicit bias can help protect it against unnecessary turnover resulting from these largely unnoticed or subconscious acts, the cumulative result of which is akin to the infamous death by a thousand cuts.

Consider this premise: It has been said that it is not the diverse individual who needs to be fixed; it is an organization’s structure and culture that needs to be addressed. That same concept applies not just in the legal profession, but in many industries.

American law firms have touted their commitment to diversity and inclusion, and statistics show that there is marginal progress on diversity in the attorney workforce from year to year, even as demands grow from clients expecting more diverse legal teams. To accelerate progress beyond marginal advances is complex for all law firms and practice areas, but the two-tiered challenge for construction lawyers is even greater. There is no easy, quick, or convenient answer.

There are difficult challenges that must be addressed in order to accelerate diversity and inclusion in construction law, and particularly so for diverse lawyers facing the two-tiered challenge in private practice. A genuine culture that supports the growth of diverse construction lawyers both in law firms and among the clients they serve, will be the key.

Florida Bar board-certified construction law attorney Melinda S. Gentile is a Miami partner at the national construction law firm of Peckar & Abramson, P.C. and serves as the firm's diversity chair and executive committee liaison. She is the co-chair of the annual Groundbreaking Women in Construction (GWIC) conference. Gentile may be reached at: mgentile@pecklaw.com.