Patent filings are on the rise in the United States. Despite regulations and precedents that have made it harder to secure patent approval in certain industries, a record-breaking 650,000 applications have been filed every year since 2016. In a number of emerging technology fields, the filing rate is even higher. Internet of Things, blockchain, AI, and medical devices have all seen strong growth over the last few years, according to a 2019 study from patent-law firm Kilpatrick Townsend.

Despite these overall upward trends and new areas of patenting opportunity, though, women remain severely underrepresented as inventors in the U.S. A 2019 report from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office found that in 2016, in only 21 percent of patents was at least one woman an inventor, up from about 7 percent in the 1980s. According to policy research organization Opportunity Insights, at the current rate of improvement, it will be another 118 years before patenting reaches gender parity in the U.S.

This gap spells trouble for both women and businesses across industries. With fewer women applying for patents, ideas from half the population are held back from benefiting consumers, society, and organizations’ bottom line. “If you only have solutions to problems that are being put forward by a homogenous group, you’re going to miss something,” says Elyse Shaw, a study director at the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR). “Diversity means more dynamic solutions, and better products and tools for people to use.”

"In some fields, like engineering, women are just way outnumbered."

“This will impact your bottom line,” Mercedes Meyer, partner at Faegre Drinker Biddle & Reath and vice-chair of the Intellectual Property Owners (IPO) Association’s Women’s Committee, says she tells the businesses she works with. “You’re losing out on inventions, you’re delaying opportunities.”

Organizations will have to do more than just flip a switch to erase the patent gender gap. A number of factors need to be addressed, from unconscious bias to underrepresentation in the heavily patenting STEM fields. But it’s not unsolvable—countries including South Korea and China have already achieved gender parity among patent applications filed through the World Intellectual Property Organization.

To close the gap, government agencies, companies, researchers, inventors, and even attorneys will need to work together to create an environment in which women inventors are not an anomaly, but the norm.

The Representation Problem

Applying for a patent can be intimidating in the best of circumstances—it often requires intense documentation, attorney oversight, hefty fees, and lots of waiting. But women in the U.S. have been underrepresented in patent filings throughout history, suggesting the existence of even more barriers to achieving the status of an inventor.

“It is a combination of factors,” says Karima Gulick, a registered patent lawyer with Gulick Law. “Women are still underrepresented in STEM and innovative industries. Most patents are issued to large companies and inventors within those large companies, so if women are still underrepresented in those fields, that number is reflected in female patent inventorship.”

The numbers, indeed, tell a similar story. According to a 2018 report from IWPR, male-owned firms are more likely to hold a patent in nearly every industry that was studied, but the difference is particularly stark in STEM fields. For example, men-owned businesses were nearly seven times as likely to hold an information-industry patent and 16 times as likely to hold a patent in mining, quarrying, or oil-and-gas extraction.

“In some fields, like engineering, women are just way outnumbered,” says Kate Gaudry, a patent attorney with Kilpatrick Townsend and coauthor of its 2019 patent-trend study. “You’re never going to have a 50 percent inventor rate in those fields until the employment situation has changed.”

Even in fields where women have better representation, there’s no guarantee that they’ll automatically begin inventing at the same rates as men.

“It’s not even the extent to which they’re employed in, say, the life sciences, but when they’re employed in the life sciences, do they have the types of jobs in these companies where they would discover something that’s potentially patentable?” Gaudry says. This type of occupational sorting, combined with a lack of precedent for female inventors, could be blocking the way for women to file for patents in their organizations, regardless of industry.

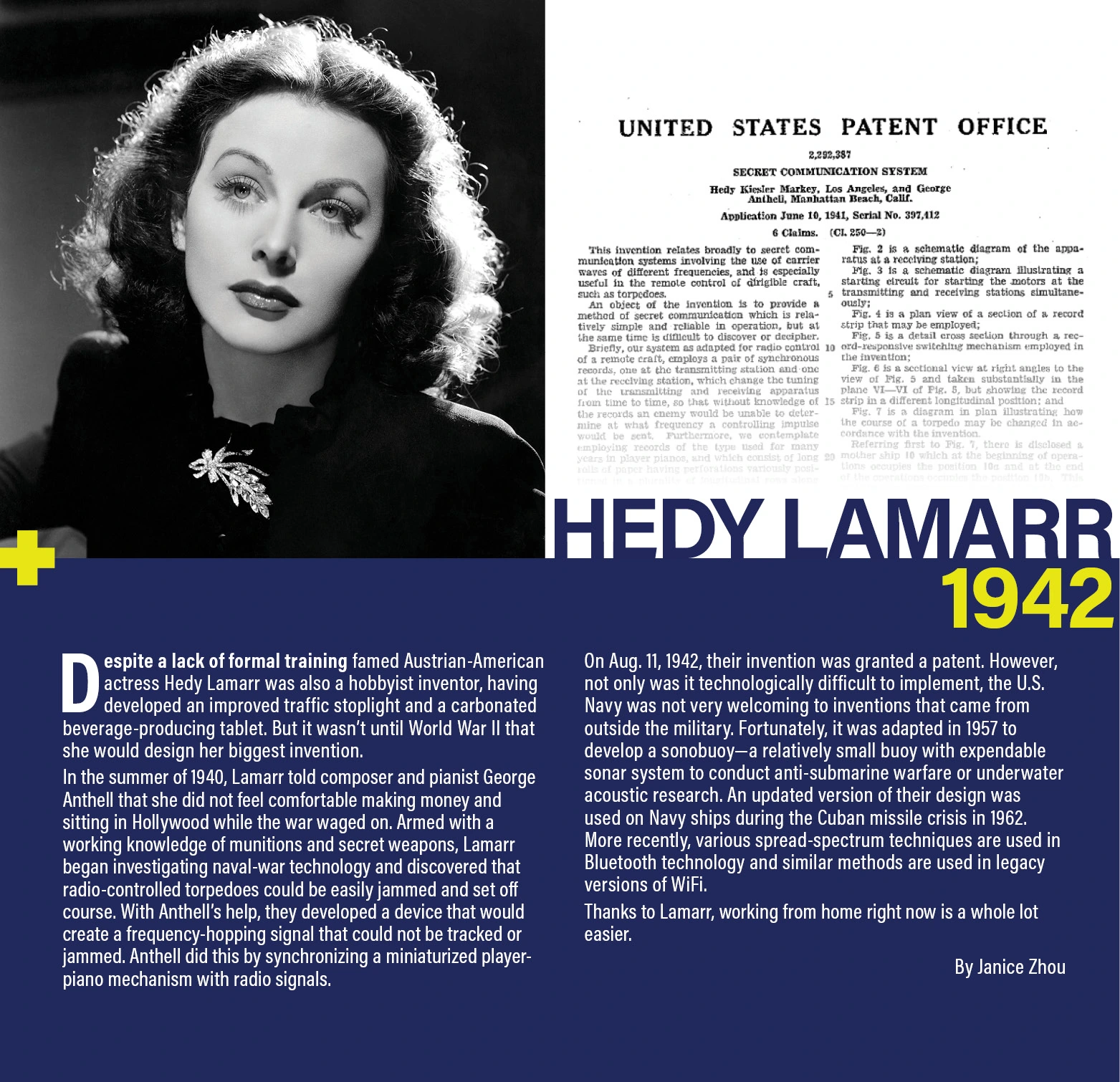

“Ask kids of any gender or race, ‘Can you name a female inventor?’ ” Meyer says. “They struggle with it. But they can name white male inventors.” It may be that because women inventors have gotten so little attention throughout history, there’s less of a road map available for women interested in inventing.

Even when female inventors do take the leap, bias may be getting in the way of their success. Researchers at Yale recently found that women inventors with common feminine names had an 8.2 percent lower chance of getting their patents approved than men did. For women with rarer names whose gender was more difficult to ascertain, the difference in approval probability fell to 2.8 percent, suggesting that conscious or unconscious bias against women can influence the approval of patents.

“In this day and age, it is likely the case that unconscious bias in the workplace, by both genders, leads to less opportunities for females, as opposed to outright discrimination,” says Stephanie Scruggs, a partner and intellectual-property attorney at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings.

Creating a Road Map

As knowledge of this gender disparity grows, a number of initiatives are being devised to address it. But before solutions can be identified, thorough and consistent information is needed to show where the problem lies, Gaudry says: “There’s a huge problem with a lack of data.

“If you have 25 percent of employees in, for example, the AI industry who are women actually working in a role where they could potentially find inventions, then a woman inventor rate of 25 percent would be good,” she explains. “The only way to increase it would be to hire more women. But if you have a situation where the organization is 80 percent women and the women inventor rate is 25 percent, that’s a very different problem to solve.”

To begin to fill in this data gap, Congress passed the SUCCESS Act in 2018 to collect data on race, gender, and veteran status during the patent application process. Other organizations, such as the IWPR, have collected their own data on women’s patenting rates. Together, these groups have been able to piece together a clearer picture of female inventors in the U.S., as well as make recommendations for how to close the gender gap.

"We have to educate so that women can say 'I can be that person, that inventor,' instead of self-selecting out of it."

In a 2018 report that Shaw coauthored, for example, the IWPR looked at organizations, nonprofits, universities, and other organizations that are making a concerted effort to empower women inventors. These success stories included workshops, startup accelerators, resources, and one-on-one coaching to help women and others navigate the patent application process.

Another approach came out of the IPO in the form of a corporate toolkit, which Meyer helped spearhead after first hearing the discouraging statistics about the patenting gender gap. The toolkit includes educational materials, as well as a step-by-step process for identifying inventor gender gaps within organizations and then addressing their root causes.

“We have to educate so that women can say ‘I can be that person, that inventor,’ instead of self-selecting out of it,” Meyer says. She has seen instances where simply reminding female scientists and engineers of the patent application process has spurred them to bring new inventions forward. Taking on this educational aspect is one way patent attorneys can play a big role in becoming a part of the solution.

“The biggest challenge is that people always assumed that the men had the ideas,” says Audrey Sherman, a division scientist at 3M, one of the companies that helped develop the IPO toolkit. “Lawyers can help women see that they really have a role in inventing. Even if her idea is a small part of the entire filing, add a claim for her. We need that.”

Meyer agrees, and believes that patent attorneys have a real responsibility to move the dial by educating and advocating for their clients. “I’m a patent attorney, so I interact with the scientists,” Meyer says. “I can help educate them about the process.

“If not us, the patent lawyers who prepare and file patent applications and prosecute them,” she continues, “then who will?”

A former senior editor at Fast Company and Oprah magazines, Kate Rockwood has decades of experience in story ideation, in-depth reporting, and writing on topics from consumer finance to health and wellness. She founded content firm Rock Top Media in 2015 to expand her ability to craft meaningful stories that connect with end readers.

Amanda Hermans is a multimedia journalist who built her editorial chops writing about environmental issues, housing and construction, and outdoor recreation for a number of consumer and trade publications. She also has extensive experience in multimedia storytelling and social media management and has directed and produced a short documentary film that was nominated for several U.S. film festivals.